Common Pregnancy, Birth & Postpartum Interventions

The most common medical interventions during pregnancy and labour are the induction of labour, regular vaginal examinations to determine extent of cervical dilation and the management of pain.

Induction of Labour

Induction of labour is when labour is artificially kick started in hospital which, according to the Royal Women’s hospital, occurs for approximately 25% of women in Australia. There are certain indications for inducing labour and in some cases it is safer to do so rather than wait for it to start spontaneously. For example, if there are concerns about the integrity of the placenta and its ability to continue nurturing the baby, if the mother has certain medical conditions such as high blood pressure, or if the baby’s growth in utero has become a concern or it is making fewer movements than it usually does and/or exhibits signs of distress.

Other reasons labour may be induced are less consistent, even from hospital to hospital as their policies can vary regarding their approach in certain scenarios. For example, when a woman goes beyond her estimated due date and even reaches 41 weeks or more, some hospitals may be more inclined to want to induce her sooner while others will encourage her to keep waiting for labour to commence spontaneously. Similarly, when a woman’s membranes break prematurely but her labour doesn’t commence immediately, her hospital has guidelines as to how long they will ‘let her wait’ before wanting to induce her to minimise the perceived risk she and the baby then have of contracting an infection. This time can vary greatly between hospitals, even in Melbourne, with some allowing women to wait for up to 24 hours and others for up to 72 hours. It is helpful for women to be aware of these discrepancies in the context of being faced with a decision whether or not to proceed with a suggested induction. A doula can help ensure they have this information. In any case, prior to proceeding with an induction, a woman’s care provider will do a vaginal examination to assess whether her cervix is favourable for the commencement of labour. This will also offer them some information about the best method to proceed with. They should also inform the woman why they believe she should be induced, what the risks are of inducing her and the possible risks to her and/or her baby’s health should she decline the induction. If this information isn’t given by the care provider routinely it can be solicited by the woman and/or her partner.

The gentlest method to induce labour is a membrane sweep, commonly referred to as a stretch and sweep. Depending on the hospital, this procedure may be offered at any time between 38 and 41 weeks of gestation, generally to avoid labour going beyond term. The procedure is carried out by the woman’s care provider who inserts a gloved finger through the vaginal canal and into the opening of the cervix where they use a circular movement in an attempt to separate the membranes from the cervix. It is understood that this triggers the release of prostaglandins that may help the cervix ‘ripen’ ready for birth which may in turn help to bring on labour. Although the procedure is gentle in comparison to other methods of inducing labour, it can be very uncomfortable for the woman and afterwards she may experience some pain and/or bleeding. If labour doesn’t commence within a couple of days after the procedure sometimes it is recommended to try it again.

Other than the membrane sweep, the primary methods used to induce labour are the following:

Artificially rupturing the membranes (ARM) by introducing an instrument into the vagina and through the cervix to make a hole in the sac of waters, which sometimes suffices to get labour started. In other cases the woman will still need medication to induce labour after her waters have been broken.

Administering syntocinon via an IV drip in order to kick-start uterine contractions. The hormone is adjusted to keep contractions regular during the extent of the labour. The baby’s heart rate is usually monitored continuously during this time by CTG. When induced this way, the mother’s mobility is restricted due to the IV line and monitoring equipment and she is unable to utilise water for pain relief.

Applying prostaglandin gel to the cervix which mimics the natural prostaglandin hormone that would otherwise be secreted by the body to prepare the cervix for labour. If the prostaglandin alone is insufficient to commence labour, doctors may suggest either trying another dose or proceeding with one of the aforementioned methods of inducing labour.

Inserting a cervical ripening balloon catheter, also known as a Foley bulb, which is gradually inflated with saline to apply pressure to the cervix and encourage it to soften. The catheter is left in place for 12 hours or so or until it falls out which would indicate that the cervix has started to open. While sometimes this method is sufficient to encourage the commencement of labour, more often than not it too is followed by either an ARM or the administration of syntocinon.

It is generally understood that labours that are induced by the above methods tend to be more painful as the body has less time to prepare and the natural adjustments in hormones to support the birthing mother’s efforts, as discussed in the previous section, are overridden. Because induced labours do tend to start more quickly and with greater intensity than spontaneous ones, evidence suggests that women who are induced are more likely to later request pain medication and they may also be more likely to need further interventions as a result, including emergency caesareans. This has become widely known as the cascade of interventions that many women experience in Australia.

Vaginal Examinations

Regular, periodic vaginal examinations in uncomplicated labours aren’t usually necessary and can generate anxiety in the labouring mother when she is found to be less dilated than she hopes after many hours of labour. It is helpful for mothers to know that they can decline these checks if they wish and it can also help for them to understand the physiological nature of cervical dilation in that it generally takes much longer to progress from 1-5 centimetres than from 5-10 centimetres for example. However, in some cases, such as when determining appropriateness of induction method or other interventions, vaginal examinations may be important.

Pain Management

The most common forms of pain medication used in Australian obstetrics today are the following:

Nitrous oxide, otherwise known as gas, inhaled through a face mask during contractions to take the edge of the intensity of the pain. The woman has complete control over the gas as she herself holds the mask and breathes the gas when she feels the need. Nitrous oxide doesn’t interfere with contractions and it is understood to be completely safe for the baby. Some women find the gas makes them feel nauseous, disoriented and/or confused and others report that it provides no relief.

Pethidine, which is a strong pain reliever, injected into a muscle or administered intravenously. The effect of the drug usually lasts for several hours and it can make the mother feel nauseous, disoriented and can alter her perception. In some cases she may also feel inadequate relief from the pain. Babies who are exposed to pethidine through the umbilical cord may experience respiratory depression and lethargy at birth, this is generally worse the sooner the baby is born after the mother was given the pethidine.

Epidural anaesthesia, which is generally the most effective form of pain relief available to women in labour, injected into the lining of the spinal cord through the back. The epidural, when administered correctly, makes the mother feel numb from the waist down but in some cases the anaesthesia is ineffective and the woman still feels discomfort. Women that have been given an epidural usually have to stay lying in bed as they lack the sensation in the legs to support them in an upright position. This lack of sensation also means that the woman is unlikely to feel when she needs to pass urine so a catheter is usually inserted. The anaesthesia may cause stress to the baby so the foetal heart rate will be monitored continuously. Risks to the mother as a result of the epidural include itchiness, tenderness at site of injection, severe and prolonged headache, ongoing numbness on the back, infection, blood clots and difficulty breathing. Further, according to the Better Health Channel, epidurals can lengthen the second stage of labour and reduce the likelihood of achieving a normal vaginal delivery.

When the mother’s lack of sensation and reduced muscle strength in her body following an epidural is such that she is unable to deliver her baby on her own, it may be suggested by her doctor that they perform an assisted/instrumental delivery by forceps or vacuum cup. Forceps are used to pull the baby out of the vagina and may be recommended if the doctor believes the mother is too exhausted to push effectively, the baby is in an awkward position or there are concerns for the baby’s wellbeing. Sometimes the forceps leave a mark on the baby’s cheeks or head which soon resolve on their own. A more common kind of assisted delivery in Australia is by vacuum cup, which is a suction device that is inserted into the vagina and placed on the baby’s head to create a vacuum. The doctor then gently pulls the other end of the device to help deliver the baby. The baby may experience bruising on the head which will once again resolve on its own. Women who have assisted deliveries are usually given an episiotomy which is a cut to the perineum to increase the size of the vaginal opening. A local anaesthetic is used to numb the area beforehand and stitches are applied afterwards. The stitches will dissolve by themselves but the woman may experience ongoing pain and complications from the scar tissue that remains.

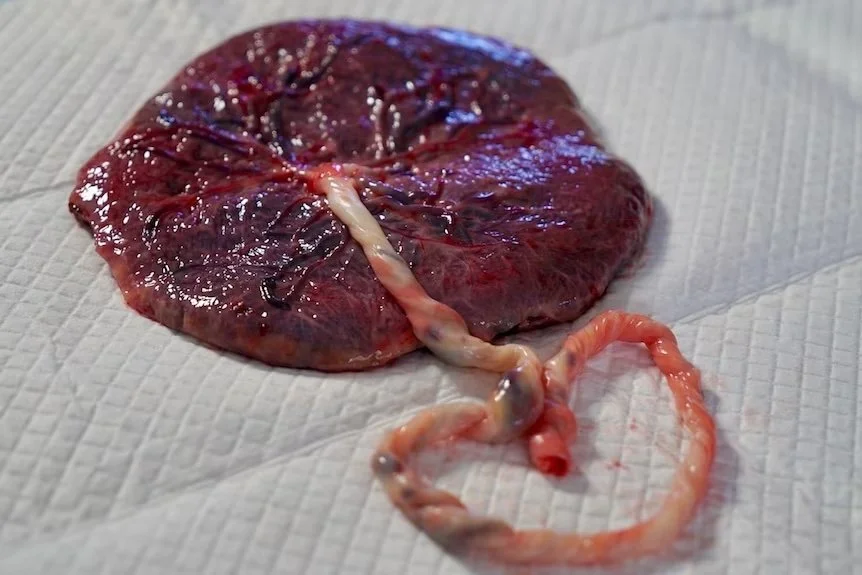

After delivery of the baby a further intervention, the active management of the third stage of labour, is often performed. This involves administering syntocinon to stimulate uterine contractions and encourage a hasty delivery of the placenta. The Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions explains that “active management was introduced to try to reduce severe blood loss at birth... [which] is a major cause of women dying in low-income countries where women are more likely to be poorly nourished, anaemic and have infectious diseases. In high-income countries, severe bleeding occurs much less often, yet active management has become standard practice in many countries”. I believe that this is a reflection of the whole tendency in contemporary obstetrics in Australia to hasten labour and delivery and approach both with an overly medicalised and pathological mindset. While it is fantastic to have access to modern medicine to hasten the third stage in cases of potential or actual haemorrhage, women should be fully informed to understand they have a choice in this procedure and that in normal, uncomplicated births they might be better off with an expectant management of the third stage, whereby their body naturally delivers the placenta when ready.

After the baby is born, the WHO recommends waiting a minimum of 60 seconds before severing the umbilical cord in order to improve maternal and infant health and nutritional outcomes. After 60 seconds, some doctors or midwives will clamp and cut the cord while others will wait for it to stop pulsating, which may even take up to five minutes or more. One of the primary benefits of this practice is the boost of the infant’s iron stores which can be topped up for several months just by waiting a few minutes before cutting the cord. If the mother and her partner wish to ensure the cutting of the umbilical cord is delayed for a given amount of time, it is important that they explicitly state this to their care providers or include it in their birth plan. The only counter indication to delayed cord clamping is when the newborn is asphixiated and in need of resuscitation. However, a new study is currently being undertaken by the Royal Women’s Hospital and Monash Medical Centre in Melbourne, whereby doctors attempt to resuscitate asphixiated babies while they’re still connected to the umbilical cord, for up to five minutes. The hospitals are currently recruiting babies to take part in this study, known as the Baby-Directed Umbilical Cord Cutting study, which has the potential to change the way doctors work with asphyxiated newborns worldwide.

If you’re a Doula or Birthworker wanting to know more about being the best you can be on the job, and turning your passion for birth into a profitable and sustainable (values aligned) business, CHECK OUT MY SUITE OF OFFERINGS!